This is the fourth and last part in a four part series on container runtimes. It’s been a while since part 1, but in that post I gave an overview of container runtimes and discussed the differences between low-level and high-level runtimes. In part 2 I went into detail on low-level container runtimes and built a simple low-level runtime. In part 3 I went up the stack and wrote about high-level container runtimes.

Kubernetes runtimes are high-level container runtimes that support the Container Runtime Interface (CRI). CRI was introduced in Kubernetes 1.5 and acts as a bridge between the kubelet and the container runtime. High-level container runtimes that want to integrate with Kubernetes are expected to implement CRI. The runtime is expected to handle the management of images and to support Kubernetes pods, as well as manage the individual containers so a Kubernetes runtime must be a high-level runtime per our definition in part 3. Low level runtimes just don’t have the necessary features. Since part 3 explains all about high-level container runtimes, I’m going to focus on CRI and introduce a few of the runtimes that support CRI in this post.

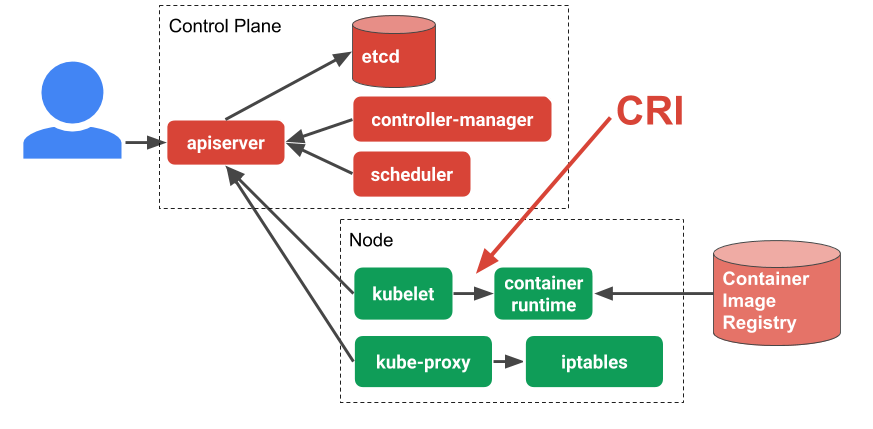

In order to understand more about CRI it’s worth taking a look at the overall Kubernetes architecture. The kubelet is an agent that sits on each worker node in the Kubernetes cluster. The kubelet is responsible for managing the container workloads for its node. When it comes to actually run the workload, the kubelet uses CRI to communicate with the container runtime running on that same node. In this way CRI is simply an abstraction layer or API that allows you to switch out container runtime implementations instead of having them built into the kubelet.

Examples of CRI Runtimes

Here are some CRI runtimes that can be used with Kubernetes.

containerd

containerd is a high-level runtime that I mentioned

in Part 3. containerd is possibly the most popular CRI runtime currently. It

implements CRI as a plugin which is

enabled by default. It listens on a unix socket by default so you can configure

crictl to connect to containerd like this:

cat <<EOF | sudo tee /etc/crictl.yaml

runtime-endpoint: unix:///run/containerd/containerd.sock

EOF

It is an interesting high-level runtime in that it supports multiple low-level

runtimes via something called a “runtime handler” starting in version 1.2. The

runtime handler is passed via a field in CRI and based on that runtime handler

containerd runs an application called a shim to start the container. This can

be used to run containers using low-level runtimes other than runc, like

gVisor,

Kata Containers, or

Nabla Containers. The runtime handler is

exposed in the Kubernetes API using the

RuntimeClass object

which is alpha in Kubernetes 1.12. There is more on containerd’s shim concept

here.

Docker

Docker support for CRI was the first to be developed and was implemented as a

shim between the kubelet and Docker. Docker has since broken out many of its

features into containerd and now supports CRI through containerd. When

modern versions of Docker are installed, containerd is installed along with

it and CRI talks directly to containerd. For that reason, Docker itself isn’t

necessary to support CRI. So you can install containerd directly or via Docker

depending on your use case.

cri-o

cri-o is a lightweight CRI runtime made as a Kubernetes specific high-level

runtime. It supports the management of

OCI compatible images and pulls

from any OCI compatible image registry. It supports runc and Clear Containers

as low-level runtimes. It supports other OCI compatible low-level runtimes in

theory, but relies on compatibility with the runc

OCI command line interface,

so in practice it isn’t as flexible as containerd’s shim API.

cri-o’s endpoint is at /var/run/crio/crio.sock by default so you can

configure crictl like so.

cat <<EOF | sudo tee /etc/crictl.yaml

runtime-endpoint: unix:///var/run/crio/crio.sock

EOF

The CRI Specification

CRI is a protocol buffers

and gRPC API. The specification is defined in a

protobuf file

in the Kubernetes repository under the kubelet. CRI defines several remote

procedure calls (RPCs) and message types. The RPCs are for operations like

“pull image” (ImageService.PullImage), “create pod”

(RuntimeService.RunPodSandbox), “create container”

(RuntimeService.CreateContainer), “start container”

(RuntimeService.StartContainer), “stop container”

(RuntimeService.StopContainer), etc.

For example, a typical interaction over CRI that starts a new Kubernetes Pod

would look something like the following (in my own form of pseudo gRPC; each

RPC would get a much bigger request object. I’m simplifying it for brevity).

The RunPodSandbox and CreateContainer RPCs return IDs in their responses

which are used in subsequent requests:

ImageService.PullImage({image: "image1"})

ImageService.PullImage({image: "image2"})

podID = RuntimeService.RunPodSandbox({name: "mypod"})

id1 = RuntimeService.CreateContainer({

pod: podID,

name: "container1",

image: "image1",

})

id2 = RuntimeService.CreateContainer({

pod: podID,

name: "container2",

image: "image2",

})

RuntimeService.StartContainer({id: id1})

RuntimeService.StartContainer({id: id2})

We can interact with a CRI runtime directly using the

crictl tool. ‘crictllets us

send gRPC messages to a CRI runtime directly from the command line. We can use

this to debug and test out CRI implementations without starting up a

full-blownkubeletor Kubernetes cluster. You can get it by downloading

acrictl` binary from the cri-tools releases

page on GitHub.

You can configure crictl by creating a configuration file under

/etc/crictl.yaml. Here you should specify the runtime’s gRPC endpoint as

either a Unix socket file (unix:///path/to/file) or a TCP endpoint

(tcp://<host>:<port>). We will use containerd for this example:

cat <<EOF | sudo tee /etc/crictl.yaml

runtime-endpoint: unix:///run/containerd/containerd.sock

EOF

Or you can specify the runtime endpoint on each command line execution:

crictl --runtime-endpoint unix:///run/containerd/containerd.sock …

Let’s run a pod with a single container with crictl. First you would tell the

runtime to pull the nginx image you need since you can’t start a container

without the image stored locally.

sudo crictl pull nginx

Next create a Pod creation request. You do this as a JSON file.

cat <<EOF | tee sandbox.json

{

"metadata": {

"name": "nginx-sandbox",

"namespace": "default",

"attempt": 1,

"uid": "hdishd83djaidwnduwk28bcsb"

},

"linux": {

},

"log_directory": "/tmp"

}

EOF

And then create the pod sandbox. We will store the ID of the sandbox as

SANDBOX_ID.

SANDBOX_ID=$(sudo crictl runp --runtime runsc sandbox.json)

Next we will create a container creation request in a JSON file.

cat <<EOF | tee container.json

{

"metadata": {

"name": "nginx"

},

"image":{

"image": "nginx"

},

"log_path":"nginx.0.log",

"linux": {

}

}

EOF

We can then create and start the container inside the Pod we created earlier.

{

CONTAINER_ID=$(sudo crictl create ${SANDBOX_ID} container.json sandbox.json)

sudo crictl start ${CONTAINER_ID}

}

You can inspect the running pod

sudo crictl inspectp ${SANDBOX_ID}

… and the running container:

sudo crictl inspect ${CONTAINER_ID}

Clean up by stopping and deleting the container:

{

sudo crictl stop ${CONTAINER_ID}

sudo crictl rm ${CONTAINER_ID}

}

And then stop and delete the Pod:

{

sudo crictl stopp ${SANDBOX_ID}

sudo crictl rmp ${SANDBOX_ID}

}

Thanks for following the series

This is the last post in the Container Runtimes series but don’t fear! There will be lots more container and Kubernetes posts in the future. Be sure to add my RSS feed or follow me on Twitter to get notified when the next blog post comes out.

Until then, you can get more involved with the Kubernetes community via these channels:

- Post and answer questions on Stack Overflow

- Follow @Kubernetesio on Twitter

- Join the Kubernetes Slack and chat with us. (I’m ianlewis so say Hi!)

- Contribute to the Kubernetes project on GitHub

If you have any suggestions or ideas for blog posts, send them to me on Twitter at @IanMLewis via either a reply or DM. Thanks!